An earlier post on "Death, Dying, and Funeral Rites In Appalachia" which I wrote about a week ago, based on some of the writing in Cratis Williams' book "Tales From Sacred Wind: Coming Of Age In Appalachia", was one of the most appealing for my readers in quite some time and I promised that I would write a more formal review of the book when I complete it which I promise I will still do. I haven't completed the book yet but I have encountered another section in it which has prompted me to write it while it is still fresh in my mind. At the time I wrote these two most recent posts about Cratis Williams, I neglected to mention in either of them that I had written a much earlier post called "Responses To Some Reading Of Cratis Williams" which might also be interesting to some of you. It is a response to a small pamphlet he wrote about his most important early teacher, William H. Vaughan, who was a primary influence in leading Williams to pursue a career in academia which was not common at the time in Eastern Kentucky.

The section in discussion here is called "Appalachian Folkways: At Play" and prompted me to remember many experiences from my own childhood growing up in Knott County in Eastern Kentucky about forty years and fifty miles from Sacred Wind where Cratis Williams spent his childhood. This section in his book is only about four pages but it contains a lot of excellent reminiscences and reminded me a great deal of my own childhood. Admittedly, Williams grew up on a dirt road in what were still, essentially, horse and buggy days. I grew up on Kentucky Route 7, a paved state highway,

+

but still in one of the more remote areas of the Big Sandy River drainage which also takes in Sacred Wind. But I grew up with a father, Ballard Hicks, who was sixty-four when I was born and about the same age as Cratis Williams' father. I was also strongly influenced by my maternal grandparents, Woots and Susie Hicks, who were actually a few years younger than my father. My mother, Mellie Hicks, was roughly the same age as Cratis Williams' mother so our major cultural influences came from people who were about the same age who had spent their lives in much the same way. Both his grandfather and my father ran small country stores for many years. Both our extended families were primarily subsistence farmers. In many ways our childhoods were the same although I do admit that I probably grew up under less financial stress than he and his siblings.

|

| Cratis Williams--Photo by The Williams Family |

+

but still in one of the more remote areas of the Big Sandy River drainage which also takes in Sacred Wind. But I grew up with a father, Ballard Hicks, who was sixty-four when I was born and about the same age as Cratis Williams' father. I was also strongly influenced by my maternal grandparents, Woots and Susie Hicks, who were actually a few years younger than my father. My mother, Mellie Hicks, was roughly the same age as Cratis Williams' mother so our major cultural influences came from people who were about the same age who had spent their lives in much the same way. Both his grandfather and my father ran small country stores for many years. Both our extended families were primarily subsistence farmers. In many ways our childhoods were the same although I do admit that I probably grew up under less financial stress than he and his siblings.

In this section of his book, he talks about the games and other forms of amusement he and his siblings and classmates benefited from as children. Many of those experiences were nearly identical to my own. My one regret about this section of his book is that he did not write more at length on this topic. In the days in which we grew up, there were no electrical toys and most of our recreation was comprised of games and amusements which required no money, no extensive use of physical equipment, and no store bought devices. He discusses attempts to catch wild game as a child and I did that also as a form of amusement more than he did. For his family, catching wild game was purely a subsistence effort. He discusses building figure four wooden triggers to set dead falls for small animals which I never learned to do. He also discusses setting homemade box traps for the same wild game such as opossums, ground hogs, rabbits, and raccoons which I and my peers also did but on a more limited basis. The box traps we all used were homemade with screen wire and/or wood and I came to know them as Hoover Boxes because they had been so named during the Great Depression by my ancestors and their peers all over America. Williams also discussed going ground hog, opossum, and racoon hunting. My father had effectively stopped hunting due to his age by the time I was old enough to go hunting but I did hunt in a limited way as a child with other members of my family and friends. But one of my most pleasant memories of my father when I was a small child, sometime before I was six, he went on what must have been one of his last squirrel hunting trips and brought back a squirrel he had shot just as it was starting to eat a hickory nut which was locked in its mouth still. I was never an effective shot with a rifle so I never became a shooter who could "bark" a squirrel but I did rabbit hunt sometimes and went coon hunting a few times with other local people. For those of you who have never heard of "barking" a squirrel, it was a practice used sometimes by expert shots with a twenty-two rifle in which they would not shoot directly at a squirrel on a tree but would judge their shot so that the bullet would strike within a quarter inch or less of the animal's head and kill it with the concussion without leaving a mark on it. By doing this, the head, in my opinion the most delicious part of a squirrel, was not harmed and you got to eat it all including the tongue and brain. In early spring, ground hog hunting was common for nearly all boys my age. All you needed was a dog which would chase and, if necessary, fight a ground hog which is not an easy task for a dog. If the ground hog made it into the hole, you could attempt to smoke it out by building a small fire in the mouth of the hole, blowing the smoke into the hole, and the animal would usually come out although sometimes it would be through a second exit from the burrow which nearly all ground dwelling animals have. Sometimes, even without a dog, you could get a ground hog if you knew where one was denning by either stalking it from fifty yards or so away and shooting it when it came out or digging it out which could sometimes be a lot of work. It was also common in my childhood for ground hog hunters in early spring to dig out litters of young ground hogs and bottle raise them as pets which Williams does not mention. My grandparents, well before I was born, had a pet ground hog for several years which I have heard many stories about. It would live at the house all spring, summer, and most of the fall and then disappear to hibernate for the winter. For several years, this ground hog whose name I don't remember, would come waddling back home when hibernation ended in early spring. I also knew several families on Beaver Creek who had, at various times, pet squirrels, raccoons, ground hogs, and flying squirrels. If you caught any of these animals when they were quite young, they all made good pets.

Cratis Williams also discussed fishing and gigging along with using either a rifle or a sledge hammer to kill fish through ice in winter. I fished and gigged all through my childhood but I had never heard of using the concussion of hitting ice with a sledge hammer to kill fish if they were visible. But I also rarely saw ice thick enough in winter to have done that if I had known about it. In my opinion, global warming had already become a mild issue in the forty years between my childhood and Williams'. Williams also discusses a game he and his peers played in the woods which they called "Fox And Hounds". It was basically a tag or chasing game in which a group of children would choose teams of "Foxes" and "Hounds" and the "Hounds" would chase the "Foxes" and try to catch them. In my childhood, any game of this nature had just become tag. Williams also discusses a war game which corresponded to our "Cowboys And Indians" which he and his peers called "Colonials And Redcoats". I and my peers had already, to a limited extent, been influenced by television and, if that game had ever existed in Knott County as it had in his native Lawrence County, it had just reverted to "Cowboys And Indians". Williams also discussed having made homemade bows and arrows from small tree branches. I saw some of this in my childhood and actually knew a family who had a son lose an eye to a homemade arrow which had been shot by one of his friends.

In the two room school in which I grew up, boys in the fourth through the eighth grades were allowed to go anywhere we wanted to for the hour of lunch so long as we could return to school in time for "Books" to be called to resume class. Most of us older boys, in that hour, would hit the woods, except for a few who had to run home to eat lunch. We would climb, run, chase each other, and swing on grape vines which we had cut at the bottom to give us a free end but leave the grapevine still attached to the tree. We also had a game which we called "Riding Out" young poplars. The better climbers would climb as high as possible up a young, slim poplar tree until they reached the point where the tree began to lean and eventually get close enough to the ground for the rider to drop off or actually just step off. If you were agile and strong, you could sometimes find a stand of young poplars on a hillside and ride from tree to tree down the hill for quite a distance. But we had one event in this game which effectively put an end to it for a long while. A neighbor boy older than me was "Riding Out" a young poplar which it turned out had a weak spot near the top. The tree broke and he fell close to fifteen or twenty feet to the ground and was unconscious for a while. The other boys carried him back to the school where he was laid on a long table which the first graders used for class and he eventually regained consciousness with some soreness and no long lasting damage. I also remember one incident in which the boys who were gathering kindling for the coal stoves in the two rooms found a copper head about two or three feet long which was nearly frozen on a cold morning after having crawled out the day before in warmer weather. They brought the poisonous snake into the classroom and laid it in front of the stove where it thawed out enough to crawl around. Then somebody picked it up with the coal shovel and threw it back out in the cold where it became stiff again. The teachers actually allowed us to bring it back into school a couple of times before it was eventually killed as I recall. I am sure that if teachers in today's world ever allowed children to "Ride Out" young trees or bring poisonous snakes into school they would be immediately fired. But not one negative word was ever said about either of these events. To our families, it was just boys being boys.

Cratis Williams also discusses what he calls "throwing" games which usually involved rocks and says one of his sisters was the best at those amusements. He says they often would throw rocks at lizards and sometimes actually catch sleeping lizards with a small stick and a noose made of skinned, limber tree bark. By the time I was in school forty years later, we had baseball and basketball with an actual basketball goal on a pole in the school yard. But our baseball game, which we and many other young Appalachians of the time called "Round Town", was played with bases made of flat rocks and a rubber ball. We rarely had any baseball gloves the rubber ball was much easier than a hard ball to catch. In the early grades from first to fourth, we boys often played "Cowboys and Indians" in the school yard with a herd of stick horses usually cut from sumac, or "shoemake", trees as Williams and I both grew up calling sumac. We even took this game to the point that we actually named our best stick horses.

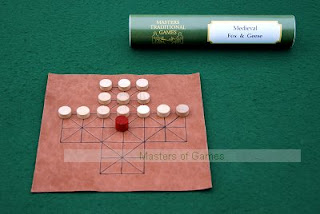

Interestingly, Cratis Williams does not talk about any kind of board game at all. By the time of my childhood, we at least had checkers and I suspect he might have also. But one of the things he reminded me of was a traditional Appalachian Folk board game which my father tried to teach me and I was not interested in enough to bother to learn it which I deeply regret. That game was called "Fox And Geese" and apparently can be traced back to Europe well before American colonization. Some experts claim it might actually be Medieval in origin. The game is played on a board which can be made of anything from tanned animal skin to cardboard to a flat piece of a wide board. The layout is a cross shaped area which is broken into five smaller areas comprised of the center section and the four wings. There is only one "Fox" and fifteen geese. When my father tried to teach me, he had drawn the board on a piece of a cardboard box from our little country store. His geese were white grains of corn and his fox was a red grain.

I have learned that there are also variations of the game with thirteen, seventeen, or twenty-two geese. According to the website which I linked above, the game is described this way: Fox & Geese is a game of inequality.

The geese cannot capture the fox but aim, through the benefit of

numbers, to hem the fox in so that he cannot move. The objective of the

fox, on the other hand, is to capture geese until it becomes impossible

for them to trap him. The geese start by occupying all 6 squares of one

arm of the cross plus the whole first adjacent row and the two end

points of the central row. The fox starts in the middle of the board. The game of Fox & Geese is played upon a cross shaped board

consisting of a 3x3 point square in the middle with four 2 x 3 point

areas adjacent to each face of the central square. This makes a total of

33 points. Pieces are allowed to move from one point to another only

along lines which join points. Accompanying the board, there should be a

single playing piece representing the fox in black or red and 15 white

playing pieces representing the geese. According to the Masters Of Games website cited above, the game is actually considered to have been rooted in medieval times. I don't know that a mathematician would say that this game is as complicated as chess but you can surely bet that it is more complicated than checkers. I never learned to play it with my father and I deeply regret having been too young and dumb to have given both of us that joy. Now, forty-nine years after my father's death, I am considering making my own board, shelling a few grains of corn, and trying to induce my wife to learn it with me. She has also become fascinated with the game and we intend to try to play it until we get some skill. The woman who cleans our house is about my age and also remembers the game being played by her father who was about 37 years younger than my father. I also knew that man before his death a few years ago, visited him numerous times, and regret that I also unknowingly lost a second opportunity to learn "Fox And Geese" from someone who grew up playing it.

|

| Fox And Geese Board--Photo by Masters Of Games |

|

| Ballard Hicks, My Father--Photo by Roger D. Hicks |